|

by Ashtyn Adams Mark 12:28-31 (NRSV) |

If we cannot attend to a lily or bird, how can we attend to our friend in need? The climate migrant that shows up to our church? Our communities as they face devastating loss due to environmental disasters? Spending time and admiring the hand of God in creation cultivates an eye for us to see the hand of God in all aspects of our lives.

This is how we love Christ, not in the abstract, not only in the classroom but in the tangible, material world. If we can first notice the ground beneath us, bless the trees around us, imitate the lilies beside us, then and only then will we begin the lifelong attempt to love God with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength.

What can I say that I have not said before?

So I’ll say it again.

The leaf has a song in it.

Stone is the face of patience.

Inside the river there is an unfinishable story

and you are somewhere in it

and it will never end until all ends.

Take your busy heart to the art museum and the

chamber of commerce

but take it also to the forest.

The song you heard singing in the leaf when you

were a child

is singing still.

I am of years lived, so far, seventy-four,

and the leaf is singing still.

Books

Weil, Simone., and Janet Martin Soskice. Waiting for God. London: Routledge, 2021.

1 Kings 3:10-12 (NRSV)

10 The Lord was pleased that Solomon had asked for this. 11 So God said to him, “Since you have asked for this and not for long life or wealth for yourself, nor have asked for the death of your enemies but for discernment in administering justice, 12 I will do what you have asked. I will give you a wise and discerning heart, so that there will never have been anyone like you, nor will there ever be.

As people seeking justice in a world succumbed to contemporary self-help traditions, which put the self at the center at the cost of the rest of the created order, desiring wisdom is vital to the survival of our planet.

The detailed account of Solomon’s building projects, accomplished through forced labor, is a demonstration of merciless political craft at the expense of the vulnerable. The agricultural extraction he implements, as Dr. Ellen Davis explains, “was a hardship on a nation of mostly subsistence farmers, managing smallholdings in a highland landscape that is marginal for an agrarian economy.” She points out the stark contrast between Solomon’s building of the temple with the equally detailed description of the building of the tabernacle in Exodus. The wilderness tabernacle was built voluntarily among men and women who brought materials with willing hearts. True wisdom is not demonstrated by Solomon, but rather Bezalel, the architect of the tabernacle, who was filled with the “spirit of God, with wisdom, with skill and knowledge in all manner of work.”

We must strive for tabernacle wisdom, a posture fully aligned with God’s intents for covenant and creation, where we see ourselves as part of a human and nonhuman community. Such wisdom respects material and human resources and affirms that there is such a thing as “enough.”

Books:

Davis, Ellen F. Opening Israel's Scriptures. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Romans 8:18-25 (NRSV)

18 I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory about to be revealed to us. 19 For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God, 20 for the creation was subjected to futility, not of its own will, but by the will of the one who subjected it, in hope 21 that the creation itself will be set free from its enslavement to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God. 22 We know that the whole creation has been groaning together as it suffers together the pains of labor, 23 and not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly while we wait for adoption, the redemption of our bodies.

Psalm 65:1-13 (NRSV)

1 Praise is due to you, O God, in Zion, and to you shall vows be performed, 2 O you who answer prayer! To you all flesh shall come. 3 When deeds of iniquity overwhelm us, you forgive our transgressions. 4 Happy are those whom you choose and bring near to live in your courts. We shall be satisfied with the goodness of your house, your holy temple. 5 By awesome deeds you answer us with deliverance, O God of our salvation; you are the hope of all the ends of the earth and of the farthest seas. 6 By your strength you established the mountains; you are girded with might. 7 You silence the roaring of the seas, the roaring of their waves, the tumult of the peoples. 8 Those who live at earth’s farthest bounds are awed by your signs; you make the gateways of the morning and the evening shout for joy. 9 You visit the earth and water it; you greatly enrich it; the river of God is full of water; you provide the people with grain, for so you have prepared it. 10 You water its furrows abundantly, settling its ridges, softening it with showers, and blessing its growth. 11 You crown the year with your bounty; your wagon tracks overflow with richness. 12 The pastures of the wilderness overflow; the hills gird themselves with joy; 13 the meadows clothe themselves with flocks; the valleys deck themselves with grain; they shout and sing together for joy.

When reading Psalm 65 in full, there is a shattering of paradoxes. The movements from silence to praise and from cult to creation, which initially seem separate, are all connected by the God enthroned in Zion. Zion theology is a fascinating part of Israel’s imagination and political ideology. “Zion” is the name associated with the religious significance of the temple King Solomon built in Jerusalem. Dr. Ellen Davis in her book Opening Israel’s Scriptures, explains how in Zion theology the temple is the garden of God, the new Eden. The entire building was styled as a sacred garden/forest, lined with fragrant woods, carved with designs, adorned with flowers. A pilgrimage to the temple would be styled as a return to Eden, meaning a return to the place where humanity was in the closet company of God, where God’s presence was most fully experienced. Part of Zion theology was thus the understanding that God had an abiding commitment to Zion. When the Babylonians attacked and the unthinkable happened as Jerusalem was forced into exile, Israel’s theology had to be reimagined (work we see mediated by the prophets). Yet, the most radical transformation of Zion theology happens in Christianity, when Zion and Jerusalem become states of beings rather than geographical locations. Jesus is himself the “meeting place” of heaven and earth, greater than the temple, where God and humanity are completely joined. Dr. Ellen Davis says, “the theology of Zion becomes the theology of the incarnation.”

Our places of worship and intimacy with God were never intended to be isolated from creation. In fact, the opposite was true: in the temple nature was honored and nurtured as a place of restoration which helped cultivate an imagination for harmonious relations with the world outside the temple.

Books:

Davis, Ellen F. Opening Israel's Scriptures. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Web Article:

https://emergencemagazine.org/feature/the-church-forests-of-ethiopia/

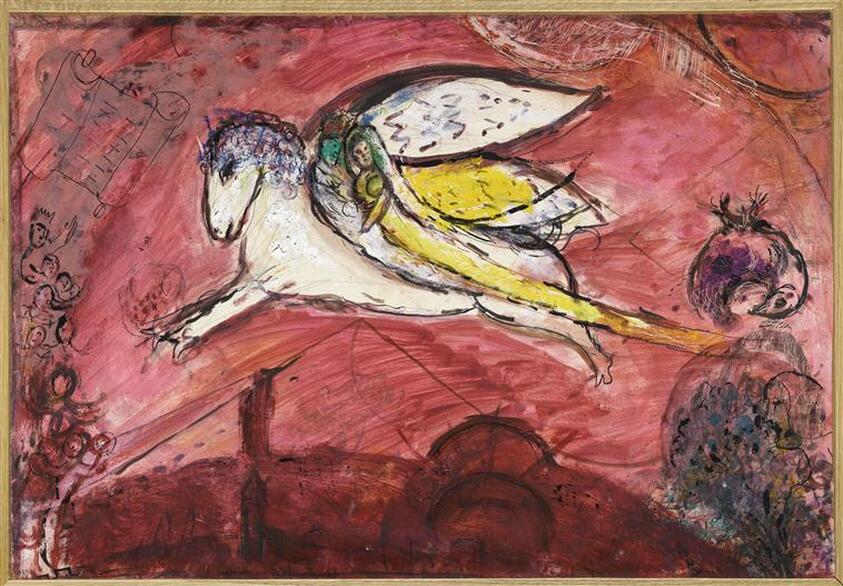

Song of Songs 2:8-13 (NRSV)

8 The voice of my beloved! Look, he comes, leaping upon the mountains, bounding over the hills. 9 My beloved is like a gazelle or a young stag. Look, there he stands behind our wall, gazing in at the windows, looking through the lattice. 10 My beloved speaks and says to me: “Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away, 11 for now the winter is past, the rain is over and gone. 12 The flowers appear on the earth; the time of singing has come, and the voice of the turtledove is heard in our land. 13 The fig tree puts forth its figs, and the vines are in blossom; they give forth fragrance. Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away.

The Song of Songs has a long interpretive history in Judaism and Christianity. Rabbi Akiva said “For all the world is not worth the day when the Song of Songs was given to Israel. For all the Writings are holy, but the Song of Songs is the Holy of Holies!” Origen famously allegorized the Song, Bernard of Clairvaux wrote 86 sermons on it while only getting to chapter three. In modernity, the Song was studied in its ancient Near Eastern context and its origins were traced back to fertility rites rejoicing in the sacred marriage of the Canaanite divine couple Ishtar and Tammuz. The Song has a rich depth and history, and continues to be full of inspiration and exhortation, especially for us in the climate crisis today.

This poem, as Robert Atler has noted, moves rapidly, without concern for unity, superimposing one image onto another and generating double entendres for us to marvel at. While the primary speaker, the Shulamite woman, speaks of her lover, the Shepherd/King, the object of her love is blurred with the overflowing abundance of creation. There is no separating the beloved from the Earth. This is important since Dr. Phyllis Trible considers the Song a depatriarchalized text which uplifts a “garden of eros,” where the configurations of gender that were established with the expulsion from the Garden of Eden are undone. She observes how the tragedy in Genesis is that the woman’s desire becomes dominion, but in the Song, male power vanishes and his desire becomes her delight. Reversal also takes place as eroticism embraces the threat of death, that not even the primeval waters of chaos can destroy. Even the animals serve Eros in the poem as the context for the joy of human sexuality rather than the tension, and there is profuse imagery which recalls the stream that watered the Earth before creation as food and water enhance life. The Shulamite ultimately becomes a “second Eve” who takes part in creating a redeeming garden of love. It invites the question, how do we become a second Eve and offer companionship to creation? The lovers treat one another and the entire land with tenderness and respect. If this is a picture of redemption, of restoration, then a harmonious creation is at the center of it along with an egalitarian relationship between the sexes. It is a testament to the intersectional work of gender and environmental justice.

It invites the question, how do we become a second Eve and offer companionship to creation? The lovers treat one another and the entire land with tenderness and respect. If this is a picture of redemption, of restoration, then a harmonious creation is at the center of it along with an egalitarian relationship between the sexes. |

Books:

Trible, Phyllis. God and the Rhetoric of Sexuality. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1986.

Pardes, Ilana. Song of Songs: A Biography. Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2019.

Matthew 9:20-23

20 Just then a woman who had been subject to bleeding for twelve years came up behind him and touched the edge of his cloak. 21 She said to herself, “If I only touch his cloak, I will be healed.” 22 Jesus turned and saw her. “Take heart, daughter,” he said, “your faith has healed you.” And the woman was healed at that moment.

There is a deep kinship between women and the Earth which witnesses to a central theme in Genesis: many creations, one Creator. Women’s menstruation is one among many ecological cycles, and, for example, most notably mimics the 28-day lunar cycle. Here, the intimate interconnectedness between our bodies and the earth from Genesis 2 is on full display: the Adam from the Adamah, the Earthing created from the Earth.

Understanding Jesus’ body as one of porous femininity is essential to our insight on the meaning and significance of the incarnation. While we ought to hold in tension how God does choose to work and love in specific, non-generic ways, this account helps us deemphasize the particularity of God becoming flesh as a Jew rather than a gentile, as a man rather than a woman. As one of my professors Dr. Chris Doran has observed, the Greek word for flesh, sarx, which appears in John’s gospel to speak of the incarnation, has its roots in the Hebrew basar, which refers to all living creatures, not just humans. I think the encounter with the bleeding woman uniquely underscores this idea in narrative form, allowing us to see how God indeed took on the stuff of living creatures, becoming a member of creation, and in this instance, a feminine, bleeding one. The incarnation is thus cosmic in scope and speaks to the goodness of creation as a whole. God is not anti-flesh or anti-world. In his book, Hope in the Age of Climate Change, Dr. Doran writes that the incarnation fully affirms that “God is the one in whom we live and move and have our being as fleshy, earthy creatures.”

Jesus does not avoid, but shares in the woman’s flow, becoming a body also marked by porosity.

There is more to be said. Mark and Luke are rich for theological discussion and research. Matthew’s redaction, in contrast, renders the woman passive and saves Jesus from the disordered and embarrassing presentation of porous femininity. We are given three short verses. Yet, attention and questions about what’s not there is as much of an important exegetical practice as to what is there. I find this month’s lectionary text in Matthew concerning the bleeding woman to still be quite pertinent to today in the sense that it testifies to a historic and tragic tendency to see female gendered blood as taboo, to look away, to forbid it in the sacred realm. Christian artwork has reinforced this gender binary time and again, with, for example, the classic images of Bathsheba bathing, presumably a ritual bath after her period has ended, but only showing her naked without any traces of blood. Mary’s priesthood is also denied in images as artists avoid showing Jesus’ birth. This is relevant because tampon and pad companies market their products on these patriarchal taboos around menstruation. Annie Dillon and Hannah Black have highlighted how disposable products dominate the industry and reinforce the status quo by promoting products as “antidotes to the shame and embarrassment women must feel about their periods. They almost always depict blue liquid rather than red blood, and avoid realistic imagery of menstruation by portraying women dancing or swimming. Some even suggest the need for women to accommodate male desires during menstruation.” The 12 billion pads and 7 billion tampons in the U.S. alone that fill up our landfills and contribute to ocean plastics cannot be separated from the messaging that women must hide, conceal, and quickly get rid of any evidence that they are experiencing their period. This is antithetical to the Jesus who freely bleeds on display and chose solidarity with the oppressed on the cross. It is well known that one of the key issues of environmental justice is that those who contribute the least to climate change suffer the most. The production process of menstrual products generates significant fossil fuel emissions, which communities of color will disproportionately bear the cost of. Promoting and providing alternative sustainable products, such as reusable menstrual cups, pads, and underwear, which have minimal impact on the planet, women’s bodies, and their wallets, may be one lasting solution that can save creation, women, and usher in the abundant life Jesus wills for us.

The 12 billion pads and 7 billion tampons in the U.S. alone that fill up our landfills and contribute to ocean plastics cannot be separated from the messaging that women must hide, conceal, and quickly get rid of any evidence that they are experiencing their period. This is antithetical to the Jesus who freely bleeds on display and chose solidarity with the oppressed on the cross.

Although traditionally concealed, menstruation is a form of participation in the divine life, a process which the God-man himself takes on. Like the ecological cycles of the Earth, it points to the Creator. It is an experience which speaks to our place within the created order, to the incarnation, and to the atonement itself.

Books:

Doran, Chris. Hope in the Age of Climate Change. Eugene: Cascade Books, 2017.

Harris, Melanie L. Ecowomanism: African American Women and Earth-Honoring Faiths.

Julian of Norwich, Revelations of Divine Love. Translated by Barry Windeatt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Moss, Candida R. “The Man with the Flow of Power: Porous Bodies in Mark 5:25-34." Journal of Biblical Literature 129, no. 3 (2010): 507–19.

Rogers, Jr, Eugene F. Blood Theology: Seeing Red in Body- and God-Talk. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Soskice, Janet M. The Kindness of God: Metaphor, Gender, and Religious Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Web Article:

https://stanfordmag.org/contents/planet-friendly-periods

Matthew 10:40-42 (NRSV)

40 “Whoever welcomes you welcomes me, and whoever welcomes me welcomes the one who sent me. 41 Whoever welcomes a prophet in the name of a prophet will receive a prophet’s reward, and whoever welcomes a righteous person in the name of a righteous person will receive the reward of the righteous, 42 and whoever gives even a cup of cold water to one of these little ones in the name of a disciple—truly I tell you, none of these will lose their reward.”

Key to these three verses in Matthew though is the designation of prophets. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel talks about how prophets are “highly disturbed individuals.” Anyone who has read the prophets might laugh at the ironic language of reward if it is equated to a modern conception, because the prophets were ostracized, exiled, and killed. You do not want to be a prophet, the one who tells the truth about the moral state of the people, who says that few are guilty, but all are responsible, who delivers judgments of God’s wrath (which is only ever a wrath against injustice and for the purposes of restoration). The ceaseless shattering of indifference is the primary task of the prophet, and that is never something encouraged among a comfortable, gluttonous people. Today in the Anthropocene, the undertaking of the prophet will still include no fringe benefits. The message that our rhythms of production and consumption mean that land, water, plants, livestock, and people are being abused will be resisted for the purposes of convenience and indulgence. Yet, the truth remains that we are failing to give the time or affection to properly nurture the gift of creation. We must cling to the promise of the prophet which has always been the same: a promise of presence, of Immanuel, God with us.

This command might hold even more significance to us in our modern age with our particular disregard for abundant and clean water. We must remember that God is not somewhere up in the clouds, but the one providing manna in the wilderness, calling prophets to critique and restore our socio-political institutions, shifting our eyes to the ones without water.

About this Blog

This blog shares the activities of Creation Justice Ministries. We educate and equip Christians to protect, restore, and rightly share God's creation.

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

October 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

June 2022

March 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

June 2019

May 2019

March 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

June 2018

April 2018

February 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

October 2016

September 2016

August 2016

July 2016

February 2016

Categories

All

Climate Justice

Conservation

Energy Ethics

Indigenous Peoples' Rights

Oceans

Public Lands

Racial Justice

Resilience

Season Of Creation

Superfund Sites

Water

RSS Feed

RSS Feed